- Home

- Jeanne Theoharis

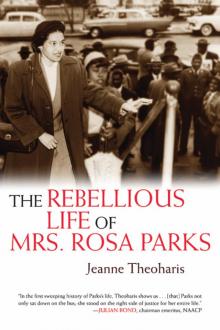

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Read online

Rosa Parks speaking at the conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march, 1965. Ralph Abernathy is on the left.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION National Honor/Public Mythology: The Passing of Rosa Parks

CHAPTER ONE “A Life History of Being Rebellious”: The Early Years of Rosa McCauley Parks

CHAPTER TWO “It Was Very Difficult to Keep Going When All Our Work Seemed to Be in Vain”: The Civil Rights Movement before the Bus Boycott

CHAPTER THREE “I Had Been Pushed As Far As I Could Stand to Be Pushed”: Rosa Parks’s Bus Stand

CHAPTER FOUR “There Lived a Great People”: The Montgomery Bus Boycott

CHAPTER FIVE “It Is Fine to Be a Heroine but the Price Is High”: The Suffering of Rosa Parks

CHAPTER SIX “The Northern Promised Land That Wasn’t”: Rosa Parks and the Black Freedom Struggle in Detroit

CHAPTER SEVEN “Any Move to Show We Are Dissatisfied”: Mrs. Parks in the Black Power Era

CONCLUSION “Racism Is Still Alive”: Negotiating the Politics of Being a Symbol

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

National Honor/Public Mythology

The Passing of Rosa Parks

ON OCTOBER 24, 2005, AFTER nearly seventy years of activism, Rosa Parks died in her home in Detroit at the age of ninety-two. Within days of her death, Representative John Conyers Jr., who had employed Parks for twenty years in his Detroit office, introduced a resolution to have her body lie in honor in the Capitol rotunda. Less than two months after Hurricane Katrina and after years of partisan rancor over the social justice issues most pressing to civil rights activists like Parks, congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle rushed to pay tribute to the “mother of the civil rights movement.” Parks would become the first woman and second African American to be granted this honor. “Awesome” was how Willis Edwards, a longtime associate who helped organize the three-state tribute, described the numbers of the people who pulled it together.1

Parks’s body was first flown to Montgomery for a public viewing and service attended by various dignitaries, including Condoleezza Rice, who affirmed that “without Mrs. Parks, I probably would not be standing here today as Secretary of State.” Then her body was flown to Washington, D.C., on a plane commanded by Lou Freeman, one of the first African American chief pilots for a commercial airline. The plane circled Montgomery twice in honor of Parks, with Freeman singing “We Shall Overcome” over the loudspeaker. “There wasn’t a dry eye in the plane,” recalled Parks’s longtime friend, federal Sixth Circuit judge Damon Keith.2 Her coffin was met in Washington by the National Guard and accompanied to its place of honor in the Capitol rotunda.

Forty thousand Americans came to the Capitol to bear witness to her passing. President and Mrs. Bush laid a wreath on her unadorned cherrywood coffin. “The Capitol Rotunda is one of America’s most powerful illustrations of the values of freedom and equality upon which our republic was founded,” Senate majority leader Bill Frist, resolution cosponsor, explained to reporters, “and allowing Mrs. Parks to lie in honor here is a testament to the impact of her life on both our nation’s history and future.” Yet, Frist claimed Parks’s stand was “not an intentional attempt to change a nation, but a singular act aimed at restoring the dignity of the individual.”3

Her body was taken from the Capitol to the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church for a public memorial before an overflowing crowd. Then her casket was returned to Detroit for another public viewing at the Museum of African American History. Thousands waited in the rain to pay their respects to one of Detroit’s finest. The seven-hour funeral celebration held at Detroit’s Greater Grace Temple on November 2 attracted four thousand mourners and a parade of speakers and singers from Bill Clinton to Aretha Franklin. In their tributes, Democratic presidential hopefuls focused on Parks’s quietness: Senator Barack Obama praised Parks as a “small, quiet woman whose name will be remembered,” while Senator Hillary Clinton spoke of the importance of “quiet Rosa Parks moments.” As thousands more waited outside to see the dramatic spectacle, a horse-drawn carriage carried Mrs. Parks’s coffin to Woodlawn Cemetery, where she was buried next to her husband and mother.4 Six weeks later, President Bush signed a bill ordering a permanent statue of Parks placed in the U.S. Capitol, the first ever of an African American, explaining, “By refusing to give in, Rosa Parks showed that one candle can light the darkness. . . . Like so many institutionalized evils, once the ugliness of these laws was held up to the light, they could not stand . . . and as a result, the cruelty and humiliation of the Jim Crow laws are now a thing of the past.”5

Parks’s passing presented an opportunity to honor a civil rights legend and to foreground the pivotal but not fully recognized work of movement women. Many sought to commemorate her commitment to racial justice and pay tribute to her courage and public service. Tens of thousands of Americans took off work and journeyed long distances to Montgomery, D.C., and Detroit to bear witness to her life and pay their respects. Across the nation, people erected alternate memorials to Mrs. Parks in homes, churches, auditoriums, and public spaces of their communities. The streets of Detroit were packed with people who, denied a place in the church, still wanted to honor her legacy.6 Awed by the numbers of people touched by Parks’s passing, friends and colleagues saw this national honor as a way to lift up the legacy of this great race woman.

Despite those powerful visions and labors, the woman who emerged in the public tribute bore only a fuzzy resemblance to Rosa Louise Parks. Described by the New York Times as the “accidental matriarch of the civil rights movement,” the Rosa Parks who surfaced in the deluge of public commentary was, in nearly every account, characterized as “quiet.” “Humble,” “dignified,” and “soft-spoken,” she was “not angry” and “never raised her voice.” Her public contribution as the “mother of the movement” was repeatedly defined by one solitary act on the bus on a long-ago December day and linked to her quietness. Held up as a national heroine but stripped of her lifelong history of activism and anger at American injustice, the Parks who emerged was a self-sacrificing mother figure for a nation who would use her death for a ritual of national redemption. In this story, the civil rights movement demonstrated the power and resilience of American democracy. Birthed from the act of a simple Montgomery seamstress, a nonviolent struggle built by ordinary people had corrected the aberration of Southern racism without overthrowing the government or engaging in a bloody revolution.7

This narrative of national redemption entailed rewriting the history of the black freedom struggle along with Parks’s own rich political history —disregarding her and others’ work in Montgomery that had tilled the ground for decades for a mass movement to flower following her 1955 bus stand. It ignored her forty years of political work in Detroit after the boycott, as well as the substance of her political philosophy, a philosophy that had commonalties with Malcolm X, Queen Mother Moore, and Ella Baker, as well as Martin Luther King Jr. The 2005 memorial celebrated Parks the individual rather than a community coming together in struggle. Reduced to one act of conscience made obvious, the long history of activism that laid the groundwork for her decision, the immense risk of her bus stand, and her labors over the 382-day boycott went largely unheralded, the happy ending replayed over and over. Her sacrifice and lifetime of political service were largely backgrounded.

Buses were crucial to the pageantry of the event and trailed her coffin around the country.8 Sixty Parks family members and dignitaries traveled from Montgomery to D.C. aboard three Metro buses draped in black bunting. In D.C., a vintage bus al

so dressed in black, along with other city buses, followed the hearse to the public memorial at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. The procession to and from the Capitol rotunda included an empty vintage 1957 bus. The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, offered free admission the day of her funeral so visitors could see the actual bus “where it all began.”

Parks’s body also served an important function, brought from Detroit to Montgomery to Washington, D.C., and then back to Detroit for everyone to witness. Her body became necessary for these public rites, a sort of public communion where Americans would visit her coffin and be sanctified. This personal moment with Parks’s body became not simply a private moment of grief and honor but also a public act of celebrating a nation that would celebrate her. Having her casket on view in the Capitol honored Parks as a national dignitary while reminding mourners that their experience was sponsored by the federal government. Look how far the nation has come, the events tacitly announced, look at what a great nation we are. A woman who had been denied a seat on the bus fifty years earlier was now lying in the Capitol. Instead of using the opportunity to illuminate and address current social inequity, the public spectacle provided an opportunity for the nation to lay to rest a national heroine and its own history of racism.

This national honor for Rosa Parks served to obscure the present injustices facing the nation. Less than two months after the shame of the federal government’s inaction during Hurricane Katrina, the public memorial for Parks provided a way to paper over those devastating images from New Orleans. Burying the history of American racism was politically useful and increasingly urgent. Parks’s body brought national absolution at a moment when government negligence and the economic and racial inequities laid bare during Katrina threatened to disrupt the idea of a color-blind America. Additionally, in the midst of a years-long war where the Pentagon had forbidden the photographing of coffins returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, Parks’s coffin was to be the one that would be seen and honored.

Friends and colleagues noted the irony of such a misappropriation. Many bemoaned the fact that some of the speakers at the memorials didn’t really know Mrs. Parks, while many friends and longtime political associates weren’t invited to participate. Some refused to go or even to watch, seeing this as an affront to the woman they had admired, while others felt troubled but attended nevertheless. Still others used the events to pay tribute to the greatness of the woman they had known. Regardless, they saw the nation squandering the opportunity to recommit itself to the task of social justice to which Parks had dedicated her life.

The public memorial promoted an inspirational fable: a long-suffering, gentle heroine challenged backward Southern villainy with the help of a faceless chorus of black boycotters and catapulted a courageous new leader, Martin Luther King Jr. into national leadership. Mrs. Parks was honored as midwife—not a leader or thinker or long-time activist—of a struggle that had long run its course. This fable is a romantic one, promoting the idea that without any preparation (political or psychic) or subsequent work a person can make great change with a single act, suffer no lasting consequences, and one day be heralded as a hero. It is also gendered, holding up a caricature of a quiet seamstress who demurely kept her seat and implicitly castigating other women, other black women, for being poor or loud or angry and therefore not appropriate for national recognition. Parks’s memorialization promoted an improbable children’s story of social change—one not-angry woman sat down and the country was galvanized—that erased the long history of collective action against racial injustice and the widespread opposition to the black freedom movement, which for decades treated Parks’s extensive political activities as “un-American.”

This fable—of an accidental midwife without a larger politics—has made Parks a household name but trapped her in the elementary school curriculum, rendering her uninteresting to many young people. The variety of struggles that Parks took part in, the ongoing nature of the campaign against racial injustice, the connections between Northern and Southern racism that she recognized, and the variety of Northern and Southern movements in which she engaged have been given short shrift in her iconization. Parks’s act was separated from a community of people who prepared the way for her action, expanded her stand into a movement, and continued with her in the struggle for justice in the decades that followed.9

This limited view of Parks has extended to the historical scholarship as well. Despite the wealth of children’s books on Parks, Douglas Brinkley’s pocket-sized, un-footnoted biography Rosa Parks: A Life and Parks’s own young-adult-focused autobiography with Jim Haskins, Rosa Parks: My Story, are the only more detailed treatments of her life and politics.10 With biographies of Abraham Lincoln numbering over a hundred and of Martin Luther King in the dozens, the lack of a scholarly monograph on Parks is notable. The trend among scholars in recent years has been to de-center Parks in the story of the early civil rights movement, focusing on the role of other activists in Montgomery; on other people, like Claudette Colvin, who had also refused to give up their seats; and on other places than Montgomery that helped give rise to a mass movement. While this has provided a much more substantive account of the boycott and the roots of the civil rights movement, Rosa Parks continues to be hidden in plain sight, celebrated and paradoxically relegated to be a hero for children.

When I began this project, people often stared at me blankly—another book on Rosa Parks? Surely there was already a substantive biography. Others assumed that the mythology of the simple, tired seamstress had long since been revealed and repudiated. Many felt confident we already knew her story—she was the NAACP secretary who’d attended Highlander Folk School and hadn’t even been the first arrested for refusing to move, they quickly recited. Some even claimed that if Rosa Parks had supported other movements, “don’t you think we would know that already.”

For my part, I had spent more than a decade documenting the untold stories of the civil rights movement in the North. This work had sought to complicate many of the false oppositions embedded in popular understandings of the movement: North versus South, civil rights versus Black Power, nonviolence versus self-defense, pre-1955 and post. When Rosa Parks died in 2005, I, like many others, was captivated and then horrified by the national spectacle made of her death. I gave a talk on its caricature of her and, by extension, its misrepresentation of the civil rights movement, decrying the funeral’s homage to a post-racial America and ill-fitting tribute to the depth of Parks’s political work. Asked to turn the talk into an article, I felt humbled and chastened. Here in the story of perhaps the most iconic heroine of the civil rights movement lay all the themes I had written about for years. And yet I kept bumping up against the gaps in the histories of her. It became clear how little we actually knew about Rosa Parks.

If we follow the actual Rosa Parks—see her decades of community activism before the boycott; take notice of the determination, terror, and loneliness of her bus stand and her steadfast work during the year of the boycott; and see her political work continue for decades following the boycott’s end—we encounter a much different “mother of the civil rights movement.” This book begins with the development of Parks’s self-respect and fierce determination as a young person, inculcated by her mother and grandparents; her schooling at Miss White’s Montgomery Industrial School for Girls; and her marriage to Raymond Parks, “the first real activist I ever met.” It follows her decades of political work before the boycott, as she and a small cadre of activists pressed to document white brutality and legal malfeasance, challenge segregation, and increase black voter registration, finding little success but determined to press on. It demonstrates that her bus arrest was part of a much longer history of bus resistance in the city by a seasoned activist frustrated with the vehemence of white resistance and the lack of a unified black movement who well understood the cost of such stands but “had been pushed as far as she could be pushed.” The community’s reaction that followed aston

ished her. And thus chapter 4 shows how a 382-day boycott resulted from collective community action, organization, and tenacity, as Parks and many other black Montgomerians worked to create and maintain the bus protest for more than a year.

The second half of the book picks up Parks’s story after the boycott. It shows the enduring cost of her bus stand for her and her family, and the decade of death threats, red-baiting, economic insecurity, and health issues that followed her arrest. Forced to leave Montgomery for Detroit, her life in the North—“the promised land that wasn’t”—is a palpable reminder that racial inequality was a national plague, not a Southern malady. Parks’s activism did not end in the South nor did it stop with the passage of the Civil and Voting Rights acts. And so the last chapters of the book illustrate the interconnections between the civil rights and Black Power movements, North and South, as Parks joined new and old comrades to oppose Northern segregation, cultivate independent black political power, impart black history, challenge police brutality and government persecution, and oppose U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

One of the greatest distortions of the Parks fable has been the ways it made her meek and missed her lifetime of progressive politics and the resolute political sensibility that identified Malcolm X as her personal hero. The many strands of black protest and radicalism ran through her life. Parks’s grandfather had been a follower of Marcus Garvey. She’d gotten her political start as a newlywed when her husband, Raymond, worked to free the Scottsboro boys, and she spent a decade with E. D. Nixon helping transform Montgomery’s NAACP into a more activist chapter. She attended Highlander Folk School to figure out how to build a local movement for desegregation and helped maintain—not simply spark—the 382-day Montgomery bus boycott. Arriving in Detroit in 1957, she spent more than half of her life fighting racial injustice in the Jim Crow North and was hired by the newly elected congressman John Conyers in 1965 to be part of his Detroit staff. Parks’s long-standing political commitments to self-defense, black history, criminal justice, and black political and community empowerment intersected with key aspects of the Black Power movement, and she took part in numerous events in the late 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, the reach of Parks’s political life embodies the breadth of the struggle for racial justice in America over the twentieth century and the scope of the roles that women played.

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks